Tomás paused in his work amid the treetops to gaze at the brilliant coral and clementine tints of the Martian sunset. His back ached from the rush of trying to finish a week’s work in four days, his gloves were sticky with tree sap and the remains of last week’s harvest, and he was developing another blister on his knife-hand. Nevertheless, a deep sense of contentment filled him. He tugged at the sweat-soaked shirt clinging to his back and breathed in the cold, early autumn breeze, wishing it would alleviate the heat enveloping him. The branches under his feet swayed, like a boat bobbing on the surf. Bending his knees to accommodate the movement of the tree, he adjusted his grip on the machete. To the east, deep thunder rolled out of a distant dust storm, the sandy winds coloring the sky the color of tea and stained teeth. Beneath it all stretched the bronze plains of open Martian desert.

Some of his friends had followed the influence of their first-generation parents, becoming scientists and doctors and such. Yet it was moments like these that made Tomás happy that he was a simple orchard gardener. He felt as though no one else got to feast upon this beauty the way he did.

Twisting around, he looked over the town’s canopy spread out behind him. Four days ago, the satellites had warned them of coming storms. Because he had lived on Mars since he was eight years old, he knew what storms could do. He’d lost more than his fair share of friends and family to the winds, and to the vines. That’s why he’d been in a rush all week, going through every yard, clearing each cedar and maple of every excess, of every dead branch. If a storm pulled one lose, that broken limb became a weapon. The impetuous young wind might plunge it into someone’s home or their precious greenhouses. It could even throw it like a spear, through another human.

Twisting around, he looked over the town’s canopy spread out behind him. Four days ago, the satellites had warned them of coming storms. Because he had lived on Mars since he was eight years old, he knew what storms could do. He’d lost more than his fair share of friends and family to the winds, and to the vines. That’s why he’d been in a rush all week, going through every yard, clearing each cedar and maple of every excess, of every dead branch. If a storm pulled one lose, that broken limb became a weapon. The impetuous young wind might plunge it into someone’s home or their precious greenhouses. It could even throw it like a spear, through another human.

“We’re as prepared as we’ll ever be, Papa,” he murmured to the sky. The trees were secure and the equipment had been stored in sheds or tied down. Everyone was ready to rush down to their basements as soon as the storm turned their way. A tall cliff stood over the spread of trees that marked the colony’s borders. He could just make out the pitched roof of Town Hall at the top and the thin, pointed nose of the rocket behind that. Even if everything went wrong, they still had an evacuation route, which was some comfort— except the idea of evacuation felt like just another kind of death.

All he could remember of Earth was his grandfather’s splintered porch in the backwoods of Mexico. He felt in his bones that cradle-instilled faith of interplanetary Manifest Destiny, and he had a hard time imagining life after it. “They’re just late-season storms,” he reminded himself.

“This colony has weathered worse.”

Turning around, he grabbed the rope and prepared to lower himself down. A shadow moved against the horizon. Tomás paused and squinted his eyes against the sun’s glare. He stared until his eyes watered and brought the shadow into focus. Someone was outside the town. Against the evening sky, a long silhouette stretched across the bare desert rock. He was so surprised he almost dropped his padre’s machete. He looked at the oncoming sandstorm and back at the figure. This far off he couldn’t recognize their face, much less the long bedraggled brown coat they wore. Who in their right mind would wander outside the colony on a storm day?

He slid his blade into its sling and began rappelling down the 200-meter tall apricot tree.

He’d never had trouble getting a tree to grow fast and abundant in the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere. Getting them to stick around long enough to produce a crop was another matter. Orange and yellow leaves brushed his arms on the way down like cold tongues of fire. If the trunk weren’t bent over like the back of a queasy man, it’d have been even taller. At the start of the season, he’d had two trees. He hadn’t expected this lopsided cripple to be the one that would survive until harvest time. He breathed in deep the sweet scent that still lingered from the late season fruit. Even though it was an ugly tree, it had given him a good harvest. But then nature often had a way of surprising him.

At last, his feet crunched into the dense gritted topsoil covering the colony grounds. He reached out reflexively and tapped his father’s funeral pole in thanks. His sister’s stood next to it. Before he’d taken two steps toward the house though he was accosted by his daughter. She’d somehow had gotten a nail head buried a centimeter deep into a pro-to chair leg. Just when he’d gotten past her, his wife called him from the kitchen hut. She insisted he help her with these heavy pots before they burned. As he did his youngest son bounded around him, shouting about some game in which his twin brother had obviously been cheating.

By the time Tomás got through them, he was starting to worry again. He walked to the back door. Who could’ve wandered so far outside the town borders when a storm watch was going on? Everyone from the desert labs had come in for harvest time, and he’d have heard if anyone had gone missing. The colony had grown to a couple of hundred people since his childhood, though it was still small by Earth standards. Secrets didn’t last long here. Perhaps someone’s kid had wandered off? He slid the front door open. It rattled in its frame and shook like it was wagging an angry finger at him.

Sitting on one of the six stumps of failed trees that marked their backyard, his mother

hummed a Corrida tune to herself, her fingers tracing up the stem of a potted mint plant. No doubt she was counting out the leaves she could not see with her milky eyes. At dinner, she would likely give him a prediction about the harvest, forgetting that it was over. It didn’t help that her predictions were almost always right.

Standing half a meter from her was the figure he’d seen on the horizon. What he thought had been an old coat was instead a strange hemp-woven robe of a kind he’d never seen before. His stomach gave a swoop even though he was no longer swaying within the tree branches. How had he gotten here so fast? With the sunlight behind them, Tomás could only make out his shape at first. He’d guessed it was one of the lanky teenagers from town, but his limbs looked overlong for even a native-born Martian. One of his arms stretched toward the old woman, a coil of hemp hanging out of his wide-knuckled fist. Tomás stepped forward. At the crunch of gravel, the young man jerked his fist behind his back and ducked his head.

Tomás frowned, his eyes adjusting. He’d never seen the boys from town wear a long knotted hemp dress, or walk over Mars with bare feet. The teenager tilted his head and glanced up at him through long matted hair. Tomás stepped back. That face! He looked just like Maria. He could feel the hairs on the back of his neck stand on end. It was impossible. Tomás realized his hands were on his padre’s machete.

He knew everyone on Mars. It wasn’t exactly a large community, but he didn’t know this boy.

His mother turned at the sound of his feet, her milky eyes twitched.

“Madre,” he heard himself say, “Step away from that boy.”

She smiled, and her crow’s feet deepened into long shadows on the sides of her face.

“Mijo,” she said. “Mijo, he says he knows Maria.” She held out her hand, groped blindly,

and gripped the boy by the forearm.

Tomás found himself stepping forward, snatching her hand from the stranger and pushing the boy to the ground.

“Who are you?” he asked. Those oh-so-familiar dark brown eyes looked up, revealing hurt and anger. Tomás felt himself pulling back from those feelings, a deep irrational fear filling him.

“He says his name’s Manuel, Tomás.” His madre sounded stern. “What did I raise you for? To treat guests like this?”

Behind him, Tomás heard the kitchen hut door hiss open. His sons tumbled out shouting but stopped and hung back, their wide eyes flickering back and forth between their father and the older boy on the ground. Felicity stepped out after them. She gaped at the stranger, who had his fists curled on the ground. Her full African mouth twisted. Her curly mahogany hair whipped across her light brown face, and her hazel eyes glared at Tomás.

“What are you doing?” his wife snapped at him.

But Tomás ignored her.

“You didn’t answer my question,” he said, his stomach tight. The boy stood up again, his hard arms moving with a youthful vibrancy that made Tomás’s backache.

“Mu-mu-Manuel,” the boy stuttered, but he succeeded in keeping his face confident. “Mi llamo Manuel.”

That small defiance in the upper lip – God, he looked just like Maria had when she and mother had been arguing! No, that wasn’t it. There was an explanation for this.

“Where did you come from? I know every face on this planet except yours, and the last settler rocket landed months ago.”

The teenager crossed his arms, face stiff, nostrils flaring. He raised one long wiry arm, his hand balled into a fist. Tomás flinched, thinking the teen was going to punch him. Then he saw a little string hanging between Manuel’s fingers. Tomás held out his hand, and Manuel dropped something cold and small into his palm. It was an “Our Lady de Fumie” medal, of the kind Bishop Miki gave out to young children at the church. In the back, scratched into the soft metal were three numbers, month, day and year, in the Martian calendar:

“6- 48-98,

10-35- 98,

10-43-98”

Tomás frowned at the boy.

He felt thin, firm fingers press into his shoulder.

“Tomás,” his wife snapped. “I don’t know what’s going on either let’s not over-react. He’s not doing anything to hurt us, Tomás. What’s gotten into you?”

But Felicity didn’t get it. She didn’t remember as clearly as he did, and his mother was too blind to see it but that boy’s face— that face was doing something terrible to him.

“Help madre,” Manuel gasped.

“Who’s in trouble?” his own madre stood up straighter, her lime green shawl slipping.

“Mi madre, Maria.”

“Oh, no!” She pressed her fingertips into her wrinkled cheeks. “Not Maria. She’s wandered off again, hasn’t she! I tried to tell her it’s dangerous.”

The old woman started rocking a little.

“I tried to warn her. Oh, I do hope she comes back soon!”

“Now you’ve set her off,” one of his young sons muttered behind him.

“Do you think he’s talking about Maria Lucia?” Adele asked, referring to one of her schoolmate’s mothers.

“What do you mean, help your madre?” said Tomás leaning forward. “Where is she? Is she outside?”

Manuel nodded.

“Oh my dear,” Felicity put her hand over Manuel’s. “I’m afraid there is nothing we can do until after the storm passes. Are you sure she didn’t make it to some shelter? She might be at a neighbor’s house.”

“Do you know where she is, Manuel?” asked Tomás. “Can you take me to her?”

Manuel nodded.

“Can I come too, Papa?” piped Adele. Tomás shook his head.

Above them, Tomás could hear the wind howling through the tree limbs. “It’s autumn,” he reminded himself, so there was still a chance. It was the summer, not the autumn storms that were the worst. Autumn storms only lasted a few hours. Sometimes summer storms lasted for as long as a week. The amber curtain covered the whole planet in sand clouds and dust devils that rose into the sky like long twisted skyscrapers. Afterward, everyone would come up out of their basements with brooms and shovels. The town would dig out their plants and homes again as if nothing happened. Rarely did anyone get stranded outside unawares anymore. If they did, finding the body was likely to be gruesome.

Once, when Tomás was younger, he and his friend Amun had been digging a ditch for some fort or other, and come across a lost skull, picked clean by the wind. It wore a miner’s helmet of the kind people used to wear back before the vines kick-started the atmosphere, back when this planet was just dust and silicon-diggers. The last storm victims had been Professor Whitehead, a teacher of his. A few weeks later, an older kid in school, Langston Freeman, and his sister Maria disappeared on the same day. They’d never found Maria’s body, but Langston’s mother was the unfortunate one to stumble across her son’s body first.

Adele and the boys might complain about all the weighted clothing Tomás made them wear, but he wasn’t about to back down. He wasn’t about to find them spread out over two square meters just because Martian gravity wouldn’t let them develop a proper bone density. And, of course, there were more dangers on Mars than just the storms. Anything might happen to a person if they strayed outside the colony borders too far for too long. He couldn’t really be considering helping the boy?

When his sister disappeared, the adults told him that the storm must’ve been what did it in the end. It’d gone on for three days after she ran off, wiping away any trace of her footprints. That’s what they told him to his face anyway. But whenever he came into a room, there was always a furtive mutter from the corner about the vines.

Tomás swallowed his fear and took the boy’s hand. His sister’s eyes stared back at him.

“Take me to her,” he said.

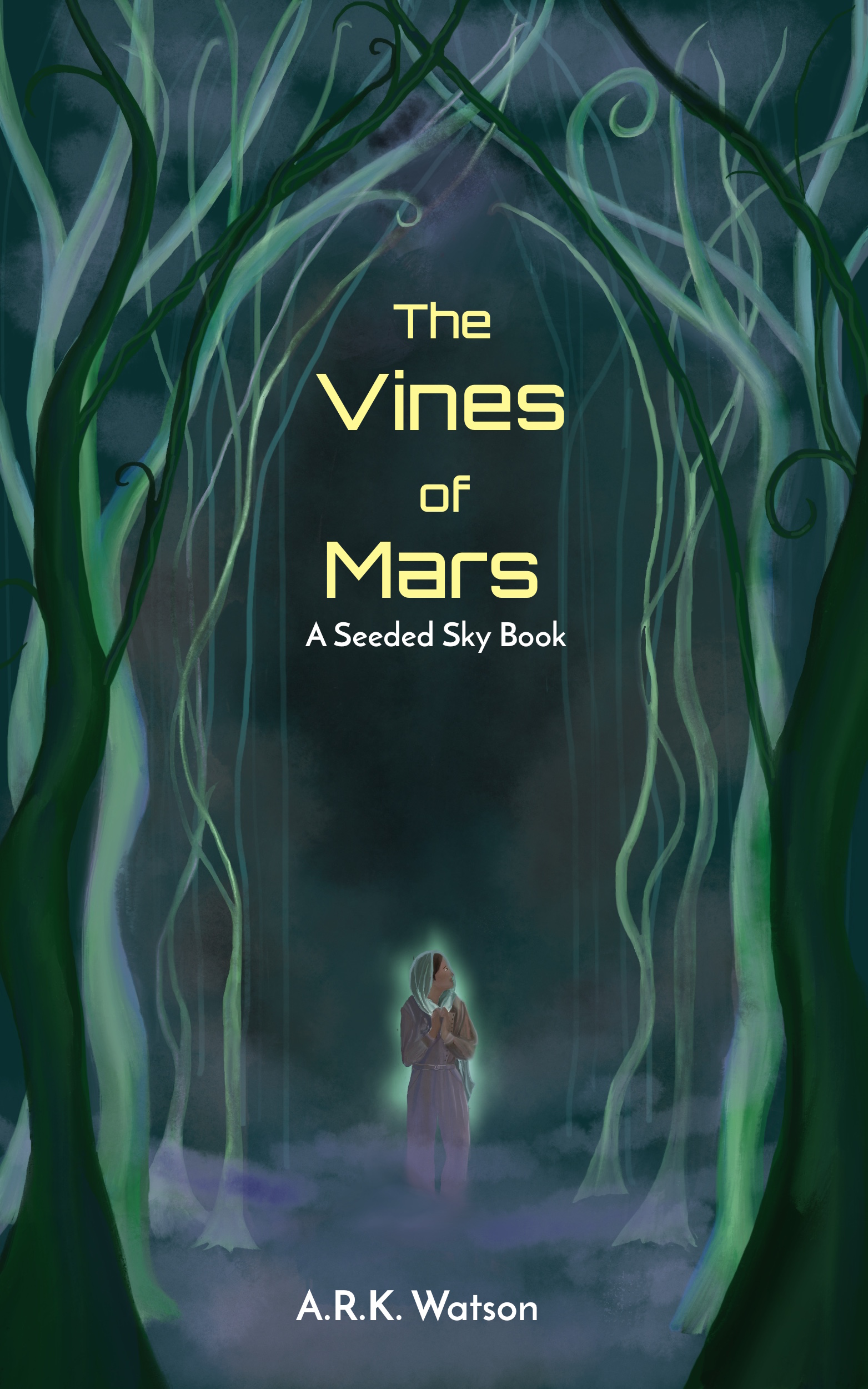

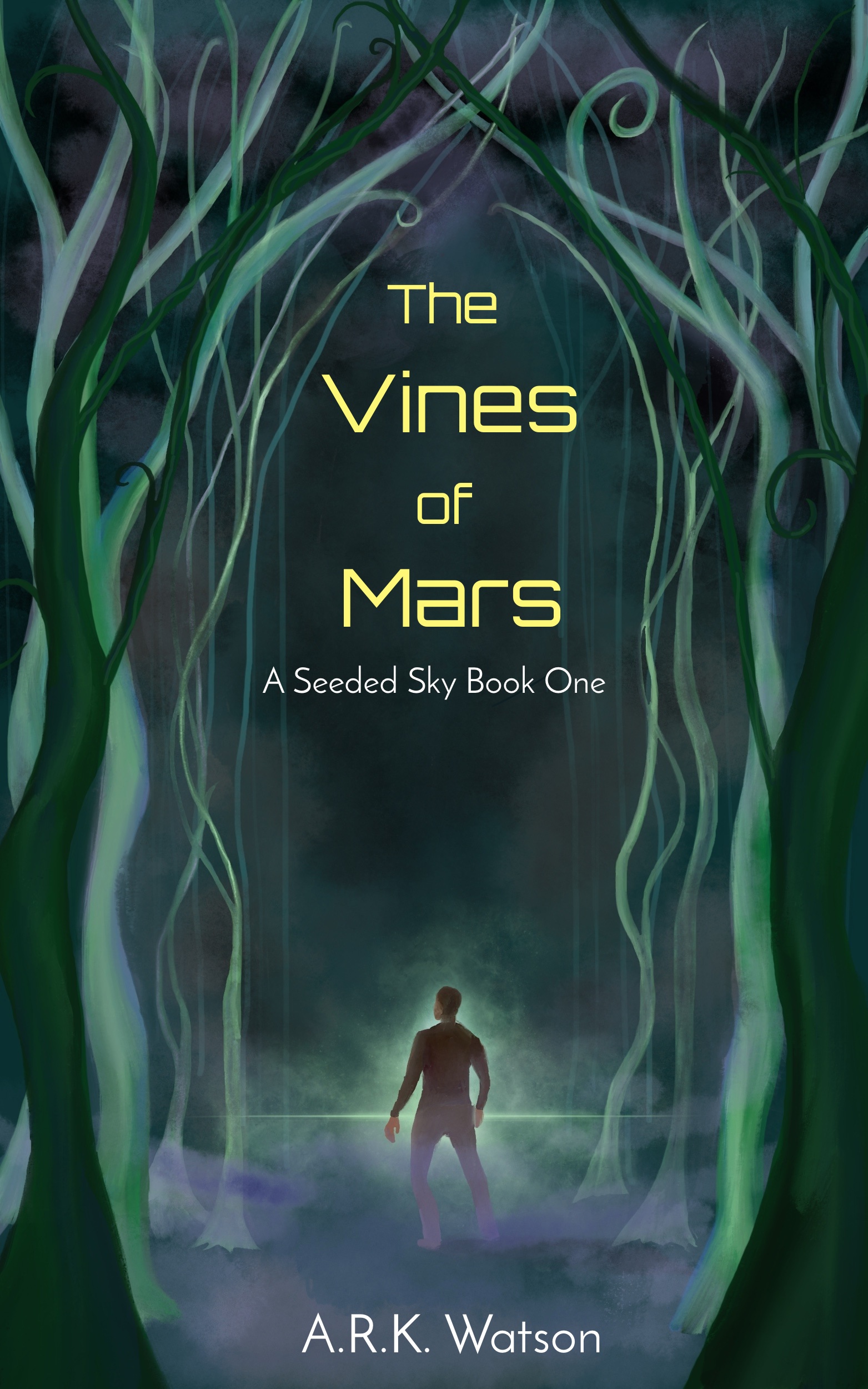

The Vines of Mars- Coming Out Sept 28th

Email Subscribers will get a free copy of the book

Chapter 2

Leaf & Bone

His wife watched him load the rover, and her hands crossed over her stomach.

Tomás brushed his hands off on his heavy lead-lined coat and threw in the last tank. He looked around for the first aid bag.

“Will you be all right here? With Abuela? I think Manuel’s story really set her off.”

“I’ll be fine, mon cheri, just promise me that if the storm catches up with you, you’ll hide out in the rover until it’s over. Don’t even think of driving through it.”

Tomás nodded. “Don’t worry, Felicity. The plating just got serviced last week. It’s not going to leak.”

His wife nodded, but a frown marred her brown face.

“Que?” he asked. When she looked like that it was better for her to just say what was on her mind.

“I just…” she looked away. “I’d almost forgotten what Maria looked like. It wasn’t until you pointed it out that I saw. And he does look like her. It’s uncanny.”

Her chin lifted and she fixed his gaze on her’s. “Promise me something else too. When you get back, that’ll be the end of this, okay? Your mother just stopped making us chase her out into the desert whenever she had one of her episodes. I don’t want to have to start chasing after you too.” She handed him the first aid kit and put her cool hand on his. “No more ghosts. No more raising the dead. You have a famille now, and a daughter who needs you. I’m tired of watching you dismiss her.” Tomás squeezed her fingers between his own to warm them. In the cold air and evening light, the smell of her was like a beacon or a lighthouse.

“What does that mean?” he asked, smiling.

“She was trying to talk to you at lunch today, and you hardly listened to a word she said.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I was distracted.”

“It’s more than that, Tomás,” said Felicity, her hazel eyes spearing him. “Would it hurt

you to help her build that chair?”

“Chair? What chair?”

“La Chaise! La Silla!” Felicity stamped her foot in frustration. “The rocking chair she’s been working on all month! She only took an interest in carpentry because she thought it would please you!”

“Rocking chair?” Tomás frowned. “She’s working on a rocking chair?”

Felicity put her face in her hands.

“I mean,” Tomás struggled, wondering what it was she wanted him to say. “It’s fine if that’s what she wants to do, but a chair? She ought to at least start with something simple, like a table or whittling. I don’t understand where she’d have gotten interested in it anyways. Maria never had the patience for it.”

“Mon Dieu!” Felicity’s curse sounded muffled in her hands. “Adele is your daughter,

Tomás. She’s nothing like Maria.” Tomás’ mouth opened and closed.

He knew that, of course. He knew he should have paid more attention to Adele earlier, but she couldn’t understand. How could he explain it to her? Maria had been gone a full two years before they started dating. He’d had time to grieve his sister by then. She’d seen his mother’s grief resurface as dementia took hold over her mind, but she’d never really understood what it had done to Tomás, what that boy’s eyes did to him now.

Felicity wasn’t there when Tomás walked in on Kaliq and Maria. Felicity never heard his family arguing about it in the kitchen, never heard Madre use anything like the word “slut,” an old-world term for “Earth girl,” she’d never lain still, pretending to sleep so Maria could have a cry in the next bed over. “It was only a bit of kissing,” she said before she left his parents framed in the doorway of the kitchen hut. The next morning Tomás woke up to the stark outline of his hermana against the horizon outside his window before his head hit the pillow again. In all the drama Maria never said a word to Tomás. But then he hadn’t known what to say to her then, and he certainly didn’t know what to say to Felicity now.

***

Manuel said he knew the way back by the landscape. They took the rover and started towards the mouth of the red skyline. Manuel directed him past the row of spread out homes along the outer ring of the town. They drove past the corn and soy fields, and around the back of the greenhouses on the Western side of town. Darkened leaves of the most recent failed soybean crop fluttered dark blue against the sinking sun. They quivered like a field of black butterflies settling over the ground, determined to suck the transplanted soil dry.

Manuel pointed out into the desert, and Tomás put the rover’s back to the failing crop. To the distant east spots of lighting flashed from within the storm’s darkness.

The speck of light that was the smaller moon, Phobos, came up over the close horizon just as they were reaching the black tree. He shivered at the sight of the bone-thin branches and told himself it was not the revealed outline of her skull that created the twisted curves and hollows of the center trunk.

The first Martians taught their children the rules to keep safe through stories. One of the first stories he’d been told was the story of the black tree. How a woman, new to the planet, ignored the rules. She had a slight cold, but she didn’t cloister herself or wear the water mask. She didn’t want to miss her first tour of the colony. Along the western border, she sneezed or spat, or hacked a boogie if your storyteller was young enough to find that funny. Whatever it was, the drop of water at her feet quivered, then disappeared beneath the ground as if sipped from a straw. A green tendril of a vine wriggled its way above the ground and wrapped around her in an instant, sucking the water out of her. The firefighters didn’t have much choice really, the poor woman was the epicenter, and it was either her life or the life of the colony. It was a frightening story, one that the adults tried to lessen by leaving out names and exact dates; wanted to make it seem an old fairy tale. In the end, it was a schoolyard rumor that told him the truth.

Tomás drew closer to the black branches that reached out of the ground like the fingers of some demon. When they passed by he crossed himself and whispered a Hail Mary.

When the smell of apricots and other Earth fruits faded, Tomás started coughing. Manuel glanced at him in confusion. Likely he was one of the new generation born with Martian-sized lungs. That was good and well for him, but Tomás pressed a button on the dash and heard the seams of the rover hiss shut, and the fan on the oxygen tank start. He leaned back in his seat, panting. He hadn’t realized how thin the air had become until he suddenly had more of it.

The hours passed in still silence, broken sometimes by Manuel’s silent gesture for him to drive in this or that direction. Manuel didn’t speak but only sat, twisting the hemp cloth of his shirt into a tighter and tighter coil as they drove. Tomás pushed the rover to its max but still unimpressive speed. It was only meant to be used as the public’s pickup truck, intended to carry objects too bulky or heavy to transport across the short thirty-minute span it took to walk to most of the colony’s central buildings. Though it did have enough energy within its solar panels to ferry scientists all the way out to the away stations and back if need be.

They’d been traveling so long into the night Tomás was beginning to think that was where Manuel was taking him. Perhaps he’d grown up isolated there? He didn’t like the idea that one of his neighbors would do that to their own kid, but it made sense. It was perhaps the only place on the planet that a person could keep someone hidden and secret. Anywhere else on Mars a person would be lucky to survive a week unaided, a vast expanse of open bare rock, ringed by the forests that covered the rest of the planet’s surface. His mother’s tireless work might’ve stopped the vines from encroaching any further, but nobody was foolish enough to go near them.

A steep cliff wall rose up over the short horizon, and Manuel gestured at him to slow down as they neared it. “Finally,” thought Tomás, thinking the boy had at last given up and realized they needed to turn back. But then something shifted in the light of the rover’s headlights. Tomás felt the blood run out of his face. The dark shadow against the night sky was not the rocky face of a cliff. He’d traveled further than he’d expected, or perhaps he’d driven too fast. The tall stems of the Martian jungle rose up in a quivering mass before him, the dark green vines disappearing into shadow beyond the rover’s headlights.

Tomás had seen pictures of the vine, he’d seen it’s black charcoal carcass after the firefighters were done with it, but he’d never seen even a live tendril before, much less been to its home. He’d heard stories of these forests, and like most colonists he dreaded them. The first team of astronauts, led by the famed first human on Mars, Captain Kateri Acorn, had been found as human skeletons wrapped in a cocoon of vines that grew like kudzu. Of all the horrors of Mars, the vine trumped them all. Attracted to any open water, the vine used to invade the colony in quick and deadly outgrowths. Back when his madre was a brilliant young scientist, she’d come up with a serum that quelled the vine’s rapid growth patterns. It was still dangerous to encounter the vine, but now it grew in slow, languorous movements, like a reluctant drunk. Now all the firefighters had to do was re-burn the boundary lines once a year around the forest’s edge, though it still made people nervous to spill water and the vines devoured every human who’d had gone past the forest perimeter without a flamethrower at hand. If the vines weren’t so vital for creating the thin breathable atmosphere the colonist would’ve burned the whole planet’s surface themselves.

After a generation growing up under threat of having their whole home swallowed overnight, where half the deaths were from storm and the other half from vine, pioneer mistrust did not dissipate with the immediate danger. Now Tomás’ children told each other ghost stories of the Marte fantasmas whose ruins and skeletons were found deep in the center. Ghosts haunted the empty places, hungry for children who strayed too far. The colonists still kept their distance, preferring the more familiar, altered and mutated Earth plants, even if they did grow unimaginably big in the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere.

“Go.”

Tomás turned. Manuel was looking at him.

“Go,” he repeated.

A doubt flicked across his mind. Did the boy mean to lead them into the forest itself?

“How much closer? If we don’t turn back soon, we’ll get caught out here until the air clears.”

Manuel looked annoyed, turned, and pushed against the rover door.

“Out,” he said. “Out! Out!”

“Hold on, hold on.” He leaned over and opened the door for him. The boy bolted out the door and started running straight for the forest.

“Hey!” Tomás leaped out of his seat, grabbing his machete from the back.

“Hey, where are you going?!” he shouted.

Something jerked his head back, and Tomás fell onto the sand. He coughed. He was still hooked to the oxygen tank in the back seat. He jumped back into the rover, slammed the door shut, and took off across the dunes after him.

The boy was fast! Tomás wasn’t going to make it. Had despair at not finding his mother given him a death wish?

A huge lightning bolt, at least a meter wide struck the next hill over and blinded him. He felt the shudder of thunder shake the sand beneath the rover’s wheels. Tomás slammed on the brakes. What if he hit Manuel by accident in his blindness? The rover skidded across the top of a dune and swung sideways. The headlights plunged into the forest border now, revealing endless woods that reached to the starry horizon and wrapped around Tomás’s planet, squeezing the human lives trapped with it. His heart fluttered like a hummingbird’s. He shook his head and saw spots. When his vision cleared the storm was breaking upon him, and Manuel was nowhere in sight.

Tomás ran a hand over his mouth and felt goose pimples on his arms. Had the lightning

got him or had the vine? Would the vine come after him next? It was still early in the storm, should he run out and try to find him?

Tomás shook his head. “No, don’t be stupid,” he muttered. He put the rover into reverse and tried to pull back. The wheels slipped on the shifting sand, and already the grainy winds were obscuring the landscape behind the windshield. He could see even the vine forest sway in the wind like a giant cat stretching its back. And then, as the scant drops of rain began to come down, the woods began to grow.

Shoots, so pale green they were almost white curled out of the ground like poisonous smoke, then became thin reeds, then arms that reached for him.

He slammed the gas and felt the rover jerk as it pulled itself back. He drove the car backward, the vines growing out to chase him. There was another jolt as he felt the rover’s back left wheel slip over something. Alarms and whistles screamed at him as he fumbled with the controls. It looked as though he’d gotten himself stuck. He’d driven reverse over a slanted boulder. The jolt had been his back wheels going over the edge. The rover was resting on its belly directly against the rock; it’s back two wheels hanging less than a meter from the ground.

He let loose a string of curse words he hadn’t known that he still remembered. The vines before him gained. They’d reach the front of the rover in another minute.

Light took him. He could hear nothing. He could see even less. When his sight finally cleared, the ground in front of his rover was scorched black. All of the screens on the rover were blinking in a pattern that didn’t instill confidence in the rover’s condition. But the vines were gone. Tomás leaned forward, trying to see outside, but the air had grown so dark it was difficult. That sudden burst of rain seemed to have stopped at least. As long as the storm stayed dry near him, he shouldn’t have to worry about the vines again.

Tomás punched the steering wheel in frustration. Now he was stuck out in the storm and even if the plating held, Manuel was likely dead already. Felicity was right. He was more out of it than he realized. He slumped back in the driver’s seat and watched the sand drift across the glass in waves until the fear and anger dissipated into a numb disappointment.

A shape moved in the vine.

Tomás sat up, hardly daring to breathe. He might be able to survive a storm in the rover, but if the forest started moving again, he’d have no chance of getting away. He couldn’t see much of the vines except what his headlights showed him in brief flashes as the sandy wind cleared and thickened again. The shape moved. Tomás leaned forward.

For a moment it looked like a strange many-limbed creature. Then Tomás realized it was Manuel and he was carrying someone wrapped in a long blanket. Tomás pushed all his safety training out of his mind and broke his promise to his wife. He opened the rover door.

Sand scraped across Tomás’s hand as he stuck it out of the door and waved. It was like moving his whole arm through a giant ball of steel wool. He yelled over the roar of the storm and waved. Manuel paused at the forest’s edge and then ran toward him. Tomás felt himself count the boy’s steps in heartbeats. Every moment the door was cracked was another moment it could get damaged. The seal could get broken, and then, once given a start; the storm would tear into their shelter in hours.

At last Manuel reached him. Tomás gritted his teeth against the pain and swung the door open fully. Manuel climbed inside with his bulky load. As soon as his feet were inside, Tomás pulled as hard as he could. Fighting the wind, he strained at the door until he heard the soft whisper of the vacuum door sealing. Then he collapsed back in his chair, breathing hard.

He felt Manuel readjust himself in the seat next to him. Tomás pushed his fear and pain away and glanced over at the boy. He was easing the blanketed form he’d been carrying into the back seat where the person could lay down. Though, other than some sand burn Manuel didn’t look injured.

Tomás shook his head and felt a shower of grit sprinkle his shoulders. A blanket of silt three centimeters thick lay over the floor bed of the rover but none of the machine’s sensors were flashing warning signs. Most of them had even begun to restart normally.

Somewhere in the back of his mind, some voice was shouting that something was wrong, but he was still too relieved to be alive to pay attention to it. “That your madre?” he asked.

Manuel nodded.

“Maria,” he said.

“Si, si, yo se,” Tomás muttered, brushing the sand off his arms and hands. He was too relieved that he and the boy were still alive to think clearly. He probably should have guessed by the shape or the smell, but he didn’t. Maybe he didn’t want to. He turned to check if their visitor was injured.

His sister’s eyes stared back at him.

She was dead. Tomás had been telling himself she was gone for years now, but he had never been able to envision it. Her eyes were open and dull from sandy winds. Her right arm splayed out at an odd angle, still clutching a thick gnarled staff. Her face – older so much older now – was calm and peaceful. The thin skin of her throat betrayed the beginning of varicose veins. Crow’s feet cracked around her eyes, but – it couldn’t be!

Tomás twisted around and clutched his head, reeling.

It couldn’t be Maria. His sister died sixteen years ago in a sandstorm. Nobody could survive a summer sandstorm. Nobody could survive the thin air outside the colony. Nobody could survive the vine.

Tomás repeated the facts to himself over and over again as though their litany alone would drive the look of those eyes out of his mind. After all, two other people had died of the same thing that year, and they’d found their bodies.

But not mine.

Tomás flinched at the whisper in his mind. He didn’t want to hear that voice, did he? He half turned to tell Manuel off for bringing him here and then stopped. He didn’t want to risk seeing the body again— her body sitting just behind him! The litany continued in his head.

No one could survive the vines. No one ever had. If there had been a way, his madre’s experiments would’ve found it.

And I wouldn’t have?

Her voice came again to him.

Or did you just imagine seeing him carry me out of there?

“Stop, stop, stop!” Tomás clutched his head again. He couldn’t even begin to take this all in now. If he was mad, he was mad because everything pointed at the impossible.

“Help.”

It was a whisper, and it wasn’t her speaking this time.

Tomás glanced to the side.

Manuel looked at him, large overgrown arms, and a young man’s voice.

“Help, please!” he gasped.

Tomás stared at the man-child. Something expanded in his chest and then collapsed.

He twisted around and saw his sister’s face again. His hand reached for hers, resting on her hard, oddly warm stomach. He felt sorrow shudder through him and that oh-so-familiar shape of her hand in his. He was drowning. Air refused to go down his throat. It entered his mouth but went no further. He could not cry. He could not make a sound or ask for help. It felt like forever before he could manage to inhale a solid breath again. Manuel’s warm hand touched his back.

The man-boy, whatever he was, looked at him with large brown eyes full of terror.

Tomás swallowed his grief. Gasping, he forced himself to exhale evenly. His hermana’s face! He hadn’t imagined it. Manuel had Maria’s — had his mother’s— exact eyes. Forcing his grief down back, he let go of his hermana’s hand, reached out and took Manuel’s. The boy was nearly a man already, but Tomás could not squash the sudden protectiveness that rose up within him. He never wanted to see those eyes look at him in terror again.

They sat there for a few moments, and Tomás began to put the pieces together in his mind.

He had heard of disgraced Earth daughters running away to the cities, but Mars had no other settlements. It had the mines for the working families, a town center, a few scattered research bases, and the jungle. The Mars settlement was “First Settlement;” a small community. Sitting on the edge of space; it had the worst and best of small-town symptoms. If Maria had gotten pregnant…

Tomás looked at Manuel. Then he reached over and, touching his sister’s face for the first time in sixteen years, closed her eyes. When he looked up, those eyes looked back at him out of the boy’s face.

“Help?” Manuel asked, soft like he was uncertain of ever getting an answer. On the way here, Tomás had thought that the boy wasn’t distressed enough for someone worried about their mother. He saw now that Manuel had been worrying so much and for so long that it had worn him down past the edge of hope and into confusion. Most likely Maria was already dead before Manuel came to the colony. The boy didn’t understand what had happened to her, but some part of him must sense it. Manuel needed someone; a father maybe, to take this from him. An adult who would know what to do next.

“Yeah,” he swallowed. “Yeah, she’s going to be fine.”

They spent the night in the darkness of the storm. Tomás held his sister’s cold fingers in one hand and his nephew’s warm one in the other. Once during the night, Tomás felt his fingers brush up against his sister’s ribs. They were warm– almost hot, where the rest of her was cold.

He raised his head and stared. Manuel lay snoozing softly next to him. He saw now how Maria’s stomach bulged unnaturally under the loose hemp tunic and through a tear in the weave he saw her skin had blistered, like a burn wound. She may have survived the storm that took her, but she didn’t die naturally. Tomás glanced at his sleeping nephew. Old tear tracks ran down his face even as he slept. Something had made his sister leave. He could chalk it up to passion, shame, and anger, but that didn’t explain the rest of it. Something, or someone, kept her from coming back. Something or someone made her stay, not even daring to talk to her family. And someone had killed her in the end. Tomás felt his fingers twitch within his sister’s cold grip, eager to wrap themselves around the neck of whoever was responsible.

The Vines of Mars- Coming Out Sept 28th

Email Subscribers will get a free copy of the book

Pink Noise by Leonid Korogodski

Pink Noise by Leonid Korogodski