What follows is the prologue from my upcoming book, The Vines of Mars.

John Crowley, award winning author and creative writing teacher at Yale University, begged me not to delete this prologue. I was uncertain at first but have kept it in in respect to his judgment.

“The second team found the astronauts’ skeletons wrapped in a coniferous cocoon of vines, their blood now feeding the flowers that bloomed around them in great cascading walls of greenery. The alien vines were what filled the air with oxygen, and warmed the atmosphere, that later her compatriots would bolster and augment as needed, directing the burgeoning environment into a second cocoon for humanity. But first, the vine sent out feelers like great intelligent Venus fly-traps, chasing the second astronauts back into their shell.

Life began on Mars the way life always begins; in a holy darkness, between communities of small hopeful stars. It formed, grew, and had it’s being long before the rest of humanity perked up from their stubbornly practical tempered wine glasses. We knew it would happen eventually; we had taken the precautions that we had the time and resources for. But like all life, it took everyone by surprise. Before the people in stiffly air-conditioned cotton collars admitted that it came for our blood, we only knew of it as a curiously large comet. It appeared out of the icy Oort cloud and winked saucy greetings at the naïve robots mining our asteroid fields. When a few lonely scientists spelled out the message on their calculators the world braced for death, and in the last minute throws of labor wrought out life. We deflected it. The moon-sized comet and its playful cloud of asteroids streaked across Bangkok’s night sky to crash instead into the face of Mars and spread its wet fingers across the expanse of two dead oceans. She watched the drama unfold in the fierce winter of break rooms, and through the screen of her media, feeling one in terror with the rest of her helpless race. She had not known they would come for her then, but first, they came for the world.

Humans in white and silver tubes, landing like locusts on the green summer dirt. Out of the flood of water that came with the comet, a thousand vines had split from the skin of the planet in the largest and most impossible desert bloom humankind had ever seen. She’d watched her family sit, stunned, around the hallowed glow of their screen, the light of a new heaven dazzling their imaginations. The reanimation of the planet’s magnetic field had been enough of an astrological anomaly– scientists were stalwart in the discipline of never using that tainted word: ‘miracle’. But it had been an invisible miracle for scientists, for the high minds that escaped the mundane and cracked open beer cans in NASA break rooms where she worked. When her toddlers rolled on the floor before the TV and laughed at the green light reflecting off each other’s faces, she knew she would leave them soon. But then the film stuttered, the voices muffled, and the signal dropped. Mars was silent and so was the first team, and she gained a little time while they searched. But even after they found blossoms burgeoning out of sockets and stomach, the second team never fully recovered the lost astronauts’ bodies.

Evaña watched from her TV screen as humanity struck back at life’s inconvenience. They brought their own plants and chose their own rivers, and burned away a wide circle of refuge. Vine-ash and rock made soil. Soil and seeded bacteria made arable land. Gas carried from the smoggiest cities of the world spread itself thin and humans walked the Mars with wonderment and copious amounts of sunscreen. And then they came to her, as she’d guessed they would eventually, and they asked her for a tree.

The officer they’d sent to convince her had peach fuzz on his upper lip. He’d talked about the future, about what an honor it was to be offered the job. To give the boy credit, he had been a wonderful poet, full of ideas and metaphors that hid behind his smile like cats. He’d called her “The Mother of Mars”, “the new ‘Demeter,'” and looked confused when she’d told him that she was already a mother. Didn’t she know how important this was? Didn’t she know this was the only salvation of man? It didn’t matter, what wars were won or lost. Life would cycle on, but in an endless, purposeless, and ultimately frail circumference if it never left that of Earth’s.

‘Frail’ was certainly an appropriate adjective. For seven days earth had lived in a state of frailty, chaos, and panic, when word of the impending comet had leaked out, but Evaña and her fellow scientists had lived in that state for three months, ever since the mining companies had reported seeing a comet the size of the Caribbean Sea hurtle past their mines toward earth, dragging along a cloud of asteroids in its gravity.

“Perhaps we had been too numbed by our success,” Evaña would think. Back in the early 21st century, it would’ve taken seven years. Now it would take no less than three years to garner enough international cooperation to throw an asteroid or a comet off course. But after their first reports they knew, for all the progress, they had much less than three years. Every day was spent waiting for the trajectory reports; every evening spent coming home, running through the door to clutch her oblivious children, to kiss her ignorant but worried husband. Eventually, the story got out. The first journalist refused to publish it once he had the truth, but the second wasn’t so clear-minded.

At first, there had been an upswing in looting and armed robberies but the robbers found the shop owners abnormally compliant. The damage to the world economy hadn’t been because of violence but because of extreme ambivalence. What was money worth when it would all burn the day after tomorrow? For seven days humanity left its work. Grocers left their doors open and unguarded, liquor sellers shared a bottle with their customers, and a group of artistically repressed stockholders made a series of papier-mâché sculptures out of their lose cash and records. After the comet had been thrown off course through a last-ditch engineering experiment, those same stockholders were-almost simultaneously- fired from their jobs, and then offered millions for their sculptures. The comet and asteroids landed instead on their red neighbor. But now it was obvious to every government official and corporate investor that humanity needed to get off this rock and on toward safer, newer ones. And wasn’t it obvious to her too? The young man’s eyes looked scandalized at her hint of disagreement, and she wanted to take all the bitter sarcasm inside her and throw it back into his stupid face.

“What was it like to come home every day and know that your children would never grow up?” she wanted to ask him. “That they would never fall in love or get married, or never learn how to fly in the hang-glider that her daughter had requested for her birthday? She’d wanted to ask the puffed-up-suit all of this, to crumple his nose and shave that stupid peach fuzz of his lip. She knew it was pointless though because after all, there was only one answer she could give.

She had known it then but still tried arguing with him. They wanted her to join the other scientists designing plants and animals that would thrive in a Martian environment and then transition over to attempting to re-engineer the vine to control its growing speed and patterns. But wasn’t there someone else who could fulfill the position? No of course not. In the field of Bioengineering only Evaña Villalobos and her teacher, crumbling Dr. Uchendu had been successful at actual creation. Most of the work in the reconstruction of the rainforest was done by other scientists who could recreate extinct plants fairly well but only she and Dr. Uchendu had been able to create entirely new life forms that fit the missing niches in the environment. “Of course she would have assistants,” he’d insisted. When the sage abuelo of modern science says that you’re the only one he would trust, the only one with the resolve and commitment to stare down the universe in the face, she can’t have expected to get off the hook so easily. At this Evaña tried cursing the white-haired Igbo, tried pretending she did not trust his judgment; would not follow him into that jungle.

Besides, it was only three years of training, said the peach fuzz above the mouth. But Evaña hadn’t cared about training. She was an academic, she’d been in school most of her life. It’d taken a few more minutes of strained conversation before he’d seen her twisting the ring on her finger. Then he told her that if her husband and children went into space training now they’d be able to join her after a separation of no less than three years. Evaña lost her nerve then. Tomȃs would be ten and Maria would be thirteen, a teenager. They would be seven and ten when she left. She would miss too much. But Evaña had already lived with the comet for three of the most painfully slow months of her life. After three months of study, she knew better than this young suit, who’d known of the comet a total of seven days. She knew her answer, the only answer she could give. She would not see her children in their childhood, but she would see them grow up. She would see them fall in love, and become whatever it was that they wanted to become. Her family, and a million families after them; all under the shade of the trees she’d genetically engineered, eating the crops she’d built in the basement of her iron-shod Martian home, eating and growing and marrying and birthing, and dying on two circumferences; twice the chance for life in relatively barren universe.”

Thank you for reading my prologue. The full book will be released Sept 28th 2020

Email List subscribers will get a free copy

Can’t Wait? Read the First Chapters Here

The second thing that happened was I received a very strange Christmas gift. I received a battered copy of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. It was from a step-relative who didn’t talk much to anyone. At first I thought the gift was some sort of passive aggressive snub, like he’d been pressured to give me something at the last minute and pulled an old copy off the shelf. But the man wasn’t by nature passive aggressive. In fact he remains the most painfully shy man I have ever met in my life. I think in the decade that I knew him I heard him speak only about five sentences. (Of course it might also be because he married one of the most talkative people I’ve ever met so it’s not like he had much opportunity to talk in the first place.) Even when I later told him I’d read the book the result wasn’t a newfound common interest upon which we could build a friendship. In fact when I told him that I had fallen head over heals for the story he only blushed a brilliant coral crimson that started at the tip of his knobbly nose and bloomed across his predominant cheekbones. Then he retreated to the other part of the house to refill his glass of sweet tea.

The second thing that happened was I received a very strange Christmas gift. I received a battered copy of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. It was from a step-relative who didn’t talk much to anyone. At first I thought the gift was some sort of passive aggressive snub, like he’d been pressured to give me something at the last minute and pulled an old copy off the shelf. But the man wasn’t by nature passive aggressive. In fact he remains the most painfully shy man I have ever met in my life. I think in the decade that I knew him I heard him speak only about five sentences. (Of course it might also be because he married one of the most talkative people I’ve ever met so it’s not like he had much opportunity to talk in the first place.) Even when I later told him I’d read the book the result wasn’t a newfound common interest upon which we could build a friendship. In fact when I told him that I had fallen head over heals for the story he only blushed a brilliant coral crimson that started at the tip of his knobbly nose and bloomed across his predominant cheekbones. Then he retreated to the other part of the house to refill his glass of sweet tea. But I didn’t need a guide after that. Having tasted this strange new world or imagination I decided that one science fiction book wasn’t enough. After all, perhaps I only liked Ray Bradbury’s style rather than the genre? So to test myself I pulled down the book my Uncle had given my brother that same Christmas; the novelization of Star Wars Episode One, The Phantom Menace by Terry Brooks.

But I didn’t need a guide after that. Having tasted this strange new world or imagination I decided that one science fiction book wasn’t enough. After all, perhaps I only liked Ray Bradbury’s style rather than the genre? So to test myself I pulled down the book my Uncle had given my brother that same Christmas; the novelization of Star Wars Episode One, The Phantom Menace by Terry Brooks.

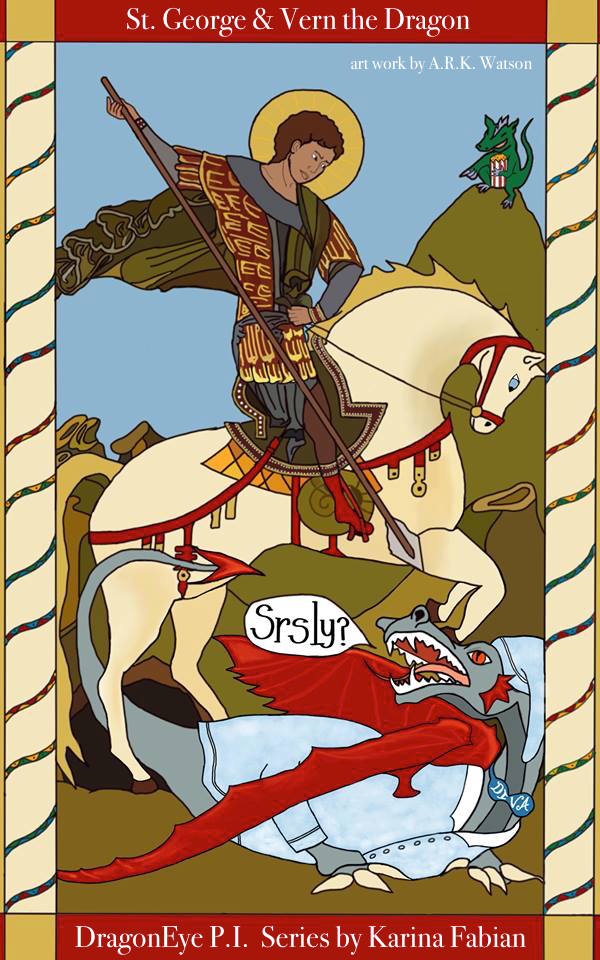

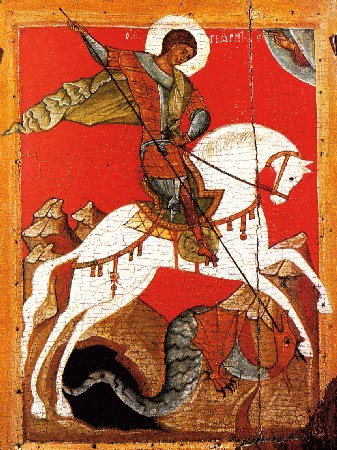

A big pet peeve of Vern’s is how everyone thinks that being a dragon is synonymous with being an evil demon. There are hints that he did have a run-in with St. George but Vern continually swears he was innocent and St. George was being an annoying paladin about everything. Given Vern’s ego, I’m sure there is more to the story. Regardless it’s been an amusing read and inspired me to make this fanart based on a medieval icon. Is that sacrilegious of me?

A big pet peeve of Vern’s is how everyone thinks that being a dragon is synonymous with being an evil demon. There are hints that he did have a run-in with St. George but Vern continually swears he was innocent and St. George was being an annoying paladin about everything. Given Vern’s ego, I’m sure there is more to the story. Regardless it’s been an amusing read and inspired me to make this fanart based on a medieval icon. Is that sacrilegious of me?